Performance of Java Logging

#Java

In the previous posts on the topic of Java Logging ( Best Practices , Logging Facades ) I already mentioned that there is a multitude of Java libraries on the topic of logging. After we clarified in the last post how to combine different loggers with a facade, we now want to look at the performance of logging libraries.

Performance Measurement in Java

To check small parts of a Java application or library by means of a benchmark, there is the Java Microbenchmark Harness (JMH) tool in Java, which is provided by the OpenJDK to perform performance benchmarks. Similar to unit tests, it executes small parts of the application (micro-benchmarks) and analyzes them. Among other things, you can set whether the code should run several times for a few seconds without measurement beforehand, in order to “warm up” the JVM and JIT.

These and other parameters can be easily defined in JMH using annotations, similar to JUnit. A simple example of a benchmark looks like this:

@Benchmark

@BenchmarkMode(Mode.Throughput)

@Warmup(iterations = 4, time = 4)

@Measurement(iterations = 4, time = 4)

public void runSingleSimpleLog() {

logger.log("Hello World");

}The example performs four warm-up runs, followed by four measurement runs. Each run lasts four seconds, and the measurement result shows how many operations per second could be performed. Specifically, this means how often “Hello World” could be logged. The whole thing is output in tabular form on the command line after the run, but it can also be saved as a JSON or CSV file, for example.

Performance Measurement for Java Loggers

Using JMH, I have created an open-source benchmark for logging frameworks that can be viewed on GitHub . It currently checks the following logging libraries or setups for their performance:

- JUL (java.util.logging) with logging to the console

- JUL (java.util.logging) with logging to a file

- JUL (java.util.logging) with logging to the console and to a file

- SLF4J Simple with logging to a file

- Log4J2 with logging to the console

- Log4J2 with logging to a file

- Log4J2 with logging to the console and to a file

- Log4J2 with asynchronous logging to a file

- Chronicle Logger with asynchronous logging to a file

For each of these constellations, there are different benchmarks that measure the performance from creating the logger to logging a simple “Hello World” message to complex logging calls (placeholder in message, marker, MDC usage, etc.).

The measurements show that logging frameworks are generally very performant. On the other hand, however, they also brought to light a few insights that are certainly not immediately clear to everyone.

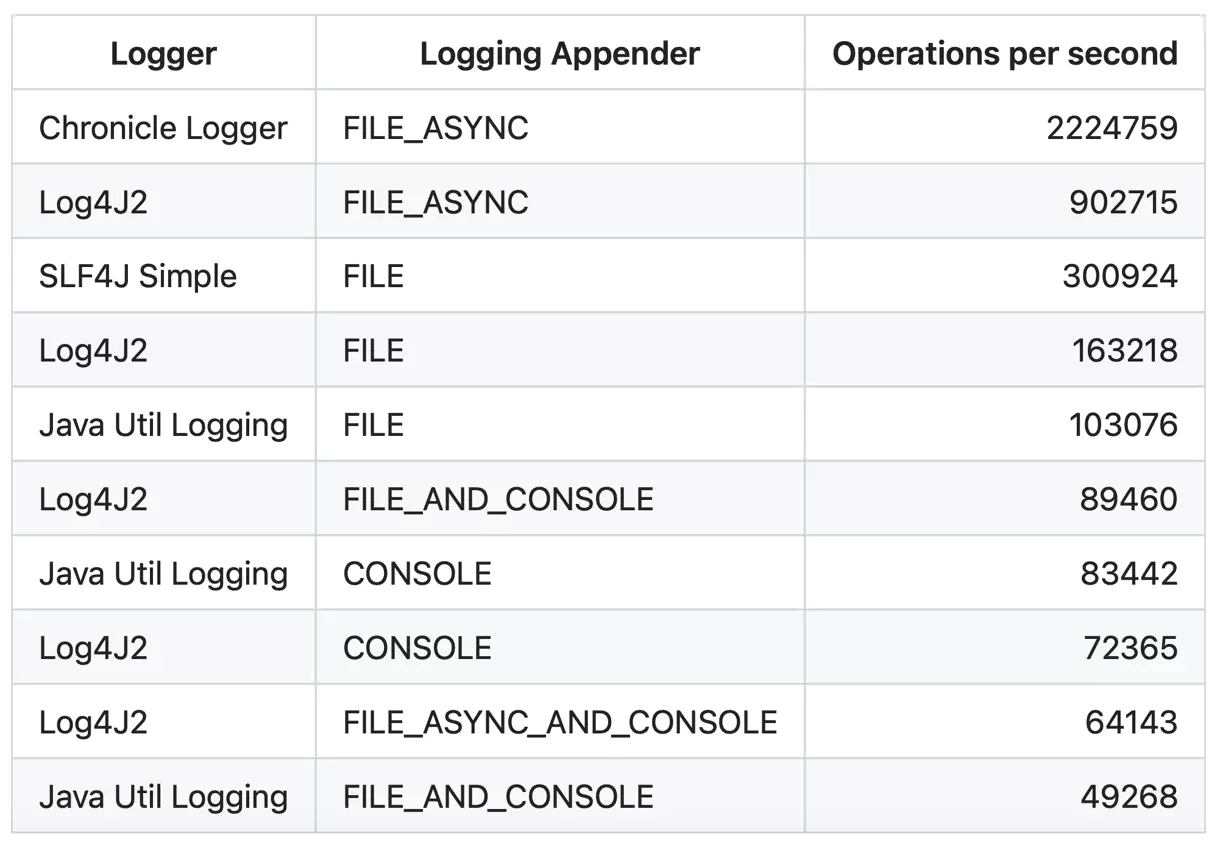

The following is an overview of measurement results for simple logging of a “Hello World” message:

The Problem with the Console

A first result of the measurements is that logging to the console is always significantly slower than logging to the file system.

While logging to a file can achieve 200,000 to 300,000 logger calls per second, console output is always well below 100,000 operations per second.

Since all logging libraries work with System.out or System.err here, it hardly makes a difference in performance which library you use.

It will be exciting to see in the future whether better performance can be achieved through tricks or modifications.

Synchronous and Asynchronous Logging to Files

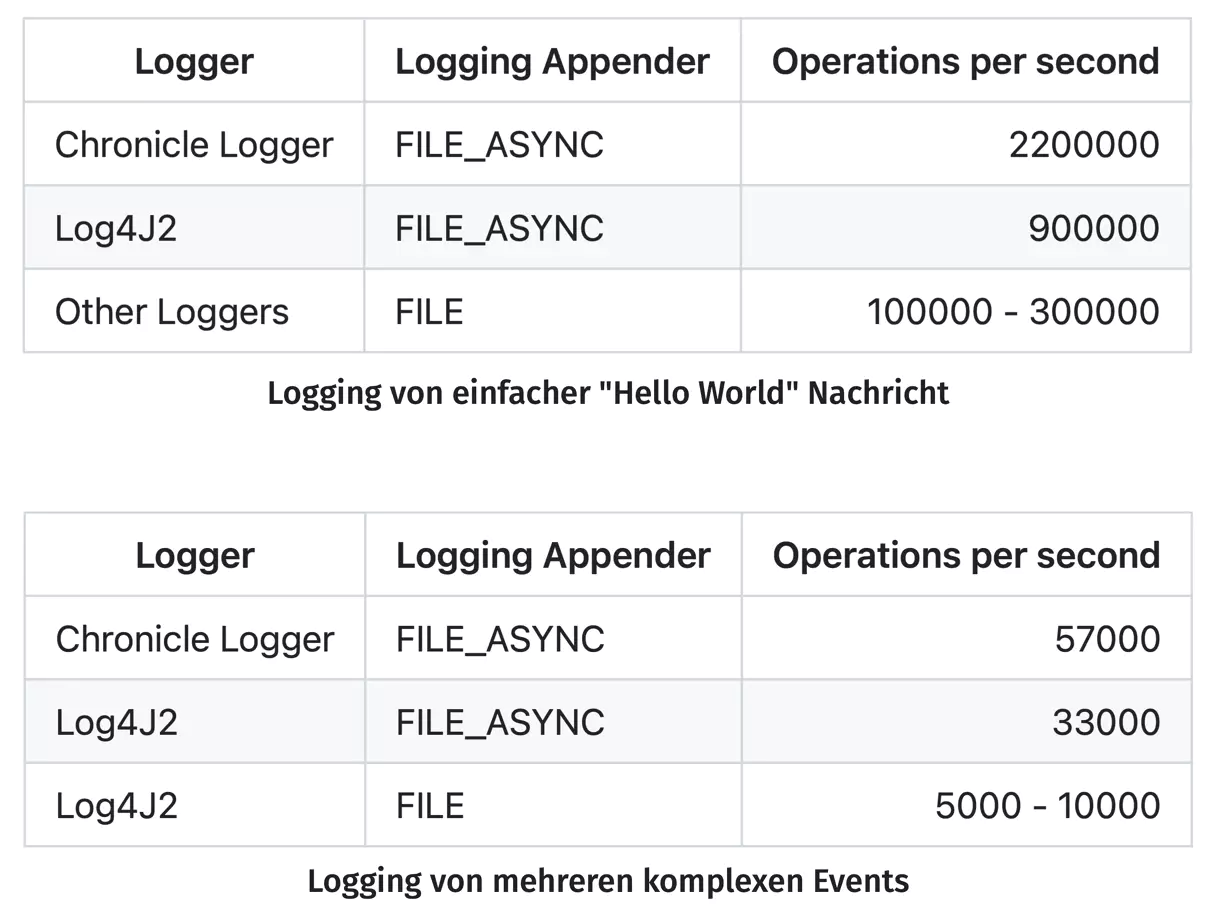

Another big difference can be seen when looking at the measurement values for synchronous versus asynchronous logging to a file. Here it immediately becomes clear that asynchronous logging is significantly faster. The following tables show the measurement values of asynchronous logging compared to synchronous logging:

The clearly higher performance is due to the fact that the write operation of the asynchronous loggers does not block. The Log4J2 and Chronicle Logger loggers use different libraries internally, but both are based on a “lock-free inter-thread communication library”. While LMAX Disruptor has to be added as a library for Log4J, which internally enables asynchronous logging via ring buffers, the Chronicle Logger is directly based on the Chronicle Queue library .

A concrete description of the internally used libraries and how they enable asynchronous communication or writing to the file system can be found in the documentation.

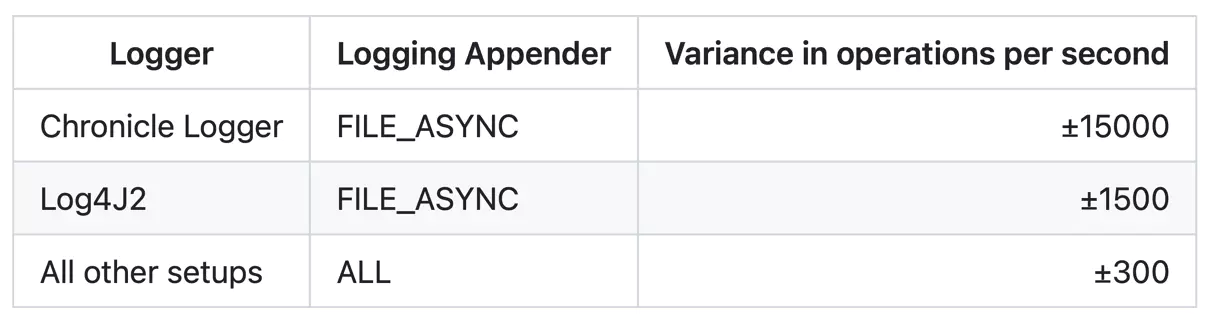

When comparing the performance of Log4J2 and Chronicle Logger, you can see that the Chronicle Logger is significantly faster. However, this performance advantage comes with a disadvantage that you need to be aware of: While Log4J2 continues to produce line-by-line, human-readable logging in the file system even in asynchronous mode, the Chronicle Logger writes all messages in a binary format. Here, tooling is then needed for reading or parsing, which the logger provides. In addition, the variance of the Chronicle Logger’s test results is significantly higher. As a reason, I suspect that the used Chronicle Queue manages the binary data for writing the logging internally and always dynamically adjusts its size. However, this still needs to be further investigated. The following table shows an overview of the variance:

Conclusion

As you can see, not only the choice of a logging library, but also its configuration is extremely important for performance. While console logging is certainly very convenient during development, you might want to consider whether the use of console logging in live operation is really always necessary. It also shows that the use of asynchronous loggers can make sense if the performance of the system is really critical. Of course, this comes with higher complexity and additional transitive dependencies. Ultimately, each project must still decide for itself which logger is most sensible. However, with the figures mentioned here, you now have another basis for determining this.

Hendrik Ebbers

Hendrik Ebbers is the founder of Open Elements. He is a Java champion, a member of JSR expert groups and a JavaOne rockstar. Hendrik is a member of the Eclipse JakartaEE working group (WG) and the Eclipse Adoptium WG. In addition, Hendrik Ebbers is a member of the Board of Directors of the Eclipse Foundation.