Best Practices and Anti-Pattern for Logging in Java and other Languages

#Java

One topic that every (Java) developer will have to deal with sooner or later is logging.

While a simple System.out.println might suffice for small example programs, learning the programming language, or quickly debugging code, it is a definite no-go for the production operation of software.

At this point, the output of an application must meet certain quality criteria to be used for verification, monitoring, and analysis of the application.

For this reason, there is a wide range of logging frameworks and APIs, and it is often not easy for developers to decide which strategy is the right one.

Therefore, I have decided to write a series of best practice articles on the topic of logging. In this post, I will start with the general basics of logging. In the near future, there will not only be an overview of the various logging frameworks in the Java ecosystem but also an insight into how to approach the topic of logging in large software architectures. The logging topic package will be rounded off with an insight into “Centralized Logging” and modern tools that allow better storage and analysis of logs.

Captain’s Log, Stardate sometime around 2022

As some might guess from the headline, I would like to briefly talk about the very basic documentation of logging. The term actually comes from the logbook used in seafaring. The logbook is generally intended to record events that occur during a sea voyage. And that’s exactly what we do with logging in an application: we write down messages about certain events during the application’s lifespan. Whether these are technically written to a log file or just output to the console, we will leave aside for now. What is important, however, is that all these messages include metadata such as the time of the event to be recorded.

Just like in seafaring, there are various very good reasons why one should rely on logging in an application. From the history in a well-maintained log, one can see why certain events were triggered. This is especially useful in IT to understand how errors occurred during the runtime of an application. But logging can be helpful not only in these problem cases. In general, one can say that logging provides information about the usage and the process of the software. This allows one to learn from the software’s past for future integrations. For example, if logging reveals that 97% of all users only click the “Like” button after using the software for a longer period, one might consider placing it more prominently in the software.

To reap the mentioned benefits from logging an application, it must be sensibly integrated into the application. To make this a bit more concrete, let’s take a look at general best practices and anti-patterns in logging.

What should I log, when, and how?

To better understand how we should use logging in our application, it is useful to carefully consider what ideally should be output by a logger. Here, I see three different categories that should always be logged:

- Important events within the application (e.g., application start or the execution of a cyclic job),

- Information coming from outside (e.g., importing data via a REST interface),

- Unexpected or faulty behavior of the application (e.g., when reading a file fails).

However, even with these categories, one should not overdo it with logging. Care must be taken not to log information in a loop. Even though user inputs are considered external inputs, one should not log every keystroke directly. The following example shows an excerpt from a problematic log history where exactly this happened:

08:34:23 User mutates id field with new value 'J'

08:34:23 User mutates id field with new value 'JA'

08:34:23 User mutates id field with new value 'JAV'

08:34:23 User mutates id field with new value 'JAVA'One can easily imagine how difficult it becomes to extract important information from a log file with such entries.

The same applies to log messages that contain too much information. Even if we know a user’s birthday, we don’t need to include this information in our log messages:

08:34:23 User 'Max' with birthday '01/01/1970' \

mutates id field with new value 'JAVA'While the username in the message can certainly be interesting for later analysis to relate this message to other log entries, the birthdate is rather distracting and makes reading the messages more complicated for the human eye.

A third important point to always keep in mind when creating log messages is data sensitivity. While we have always seen the change of an ID in the log in the previous messages, the following message should never appear in a log file:

08:34:23 User 'Max' mutates password with new value '12#Agj!j7In this case, logging would represent a real security vulnerability of the application. Sensitive data such as the user’s password should, of course, never be visible in log messages.

Based on the previous insights, the following log messages appear sensible and well-structured:

08:34:23 User 'Max' mutates id field with new value 'JAVA'

08:34:23 User 'Max' mutates passwordIn addition to these tips, one should always ensure that the source code of an application is not so cluttered with log calls that the source code becomes unreadable and difficult to understand. The following snippet from a Java program shows what happens when logging calls are overdone:

LOG.log("We start the transaction");

manager.beginTransaction();

LOG.log("DB query will be executed");

LOG.log("DB query: select * from users");

long start = now();

users = manager.query("select * from users");

LOG.log("DB query executed");

LOG.log("DB query executed in " + (now() - start) + " ms");

LOG.log("Found " + users.size() + " entities");

manager.endTransaction();

LOG.log("Transaction done");Here, the code and its exact function are hardly recognizable. Without the logging calls, we can understand it at a single glance:

manager.beginTransaction();

users = manager.query("select * from users");

manager.endTransaction();However, one should not completely omit logging, and perhaps this is exactly a place where one would like to see a lot of information in the logs.

In this case, logging calls must be cleverly integrated into the structure and API of the application.

All the information we saw in the first example could also be logged directly within the beginTransaction, query, and endTransaction methods.

This way, the business logic is cleaned of logging calls, and we still get all the information.

If it is not possible to place logging directly in the API for various reasons, complexity related to logging can also be relatively easily “hidden” in reusable lambdas or methods. The following example shows a generic function that executes a query within a transaction and continues to provide all necessary information as log messages:

final Function<String, T> queryInTransaction = query -> {

LOG.log("We start the transaction");

manager.beginTransaction();

LOG.log("DB query: " + query);

long start = now();

T result = manager.query(query);

LOG.log("DB query found " + result.size() + " entities in "

+ (now() - start) + " ms");

manager.endTransaction();

LOG.log("Transaction done");

return result;

}This allows us to call our operations in a readable form with maximum logging in the business logic:

LOG.log("Loading all users from database");

users = queryInTransaction("select * from users");Anyone who has ever worked with logging frameworks will certainly miss the logging level as an important and central element in the previous examples. We will take a closer look at this to conclude. Although different loggers do not always define the same levels, they all have the same functionality: on a one-dimensional scale, the level indicates how important the message is in the context of all messages.

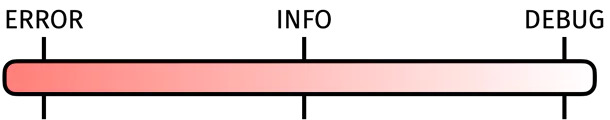

As shown in the example image, let’s assume we can use three different levels in our logging (note: depending on the specific logging framework, there are several more).

At the ERROR level, we want to log all faulty behavior of the application, while we use the INFO level for general information about the application’s process and status.

With the DEBUG level, we log detailed information that is only important in exceptional cases.

Java source code that uses the different levels in logging could look like this:

try {

LOG.info("Loading all users from database");

users = query("select * from users");

LOG.debug("Found " + users.size() + " users in db");

} catch (Exception e) {

LOG.error("Error while loading all users");

}At runtime, the logger’s level can be configured to filter which messages should actually end up in the log.

Typically, messages at the DEBUG level are filtered out and only included in the log during error analysis or similar scenarios.

The advantage is that the application’s source code does not need to be changed to obtain more information.

Only the configuration needs to be adjusted, and this can even happen dynamically at runtime depending on the logging framework used.

Additionally, such filtering can also be used to log different information in a test or production system.

A final logging concept

Based on the general rules outlined in this blog post, you can already start defining logging practices for an application or an entire system landscape. Important questions to consider when creating logging rules include:

- Who will read the log file?

- What do you want to learn or extract from the logs?

- What do you NOT want to extract from the logs?

- Should there be differences in logging between different environments (Test/Production)?

As described, there are various points to consider when it comes to logging. Generally, it is advisable to define a concept for handling logging. This concept can include guidelines and best practices for internal logging management. It should also cover technical aspects such as preferred libraries or patterns. We will take a closer look at these in the next part of the series on Java logging.

Hendrik Ebbers

Hendrik Ebbers is the founder of Open Elements. He is a Java champion, a member of JSR expert groups and a JavaOne rockstar. Hendrik is a member of the Eclipse JakartaEE working group (WG) and the Eclipse Adoptium WG. In addition, Hendrik Ebbers is a member of the Board of Directors of the Eclipse Foundation.