Gaming & Web3 - How an Open and Secure Future of Ownership in Games Could Look

#web3

The use of Web3 technologies in the gaming industry is still in its infancy. Although there is a vision that assets, e.g. items and skins, obtained in video games can be owned independently of the game and used in other games, this reality is still nowhere to be found. In this article, I want to take a closer look at non-fungible tokens (NFTs) and their usability for video games and consider what further standardizations are needed to realize the promise of game-independent assets.

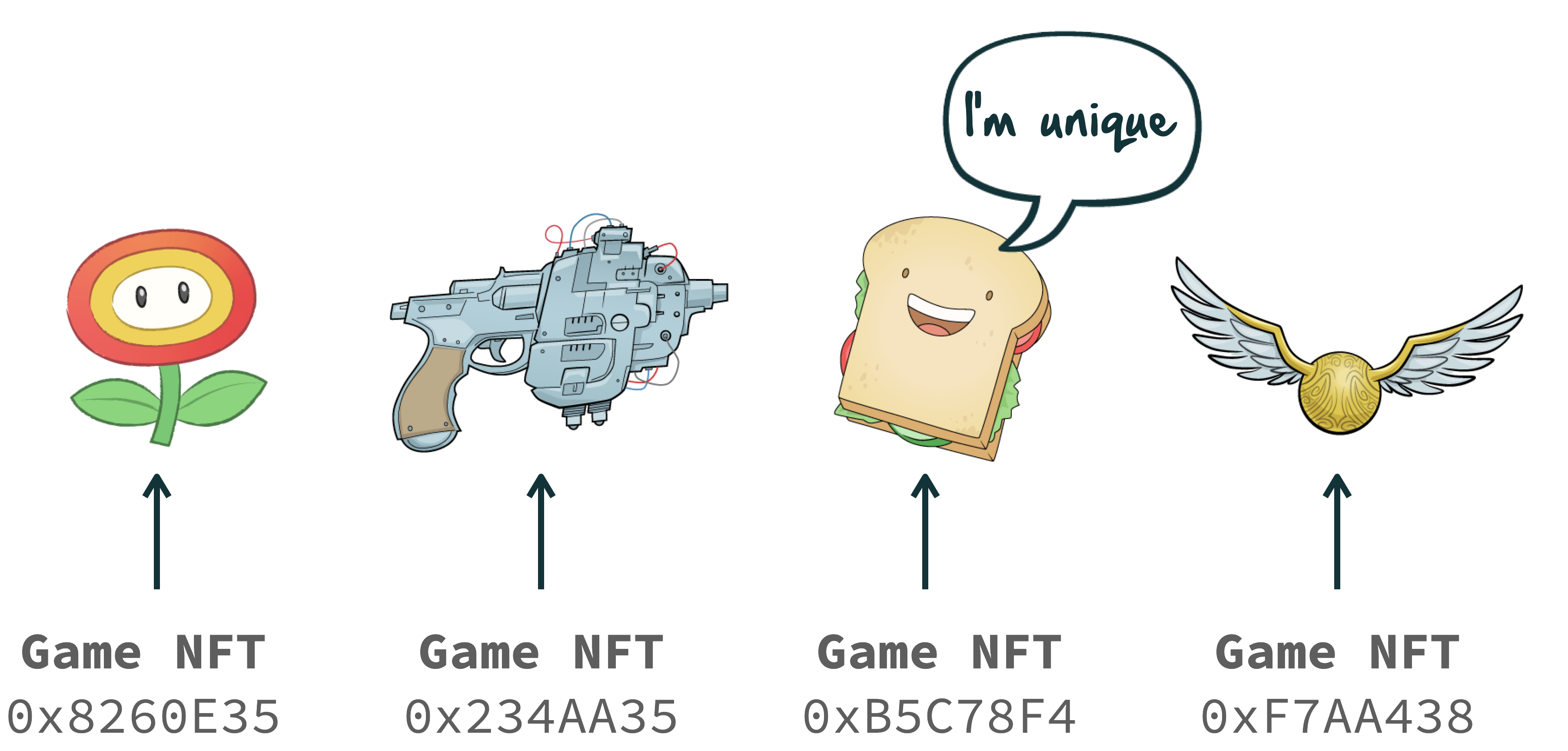

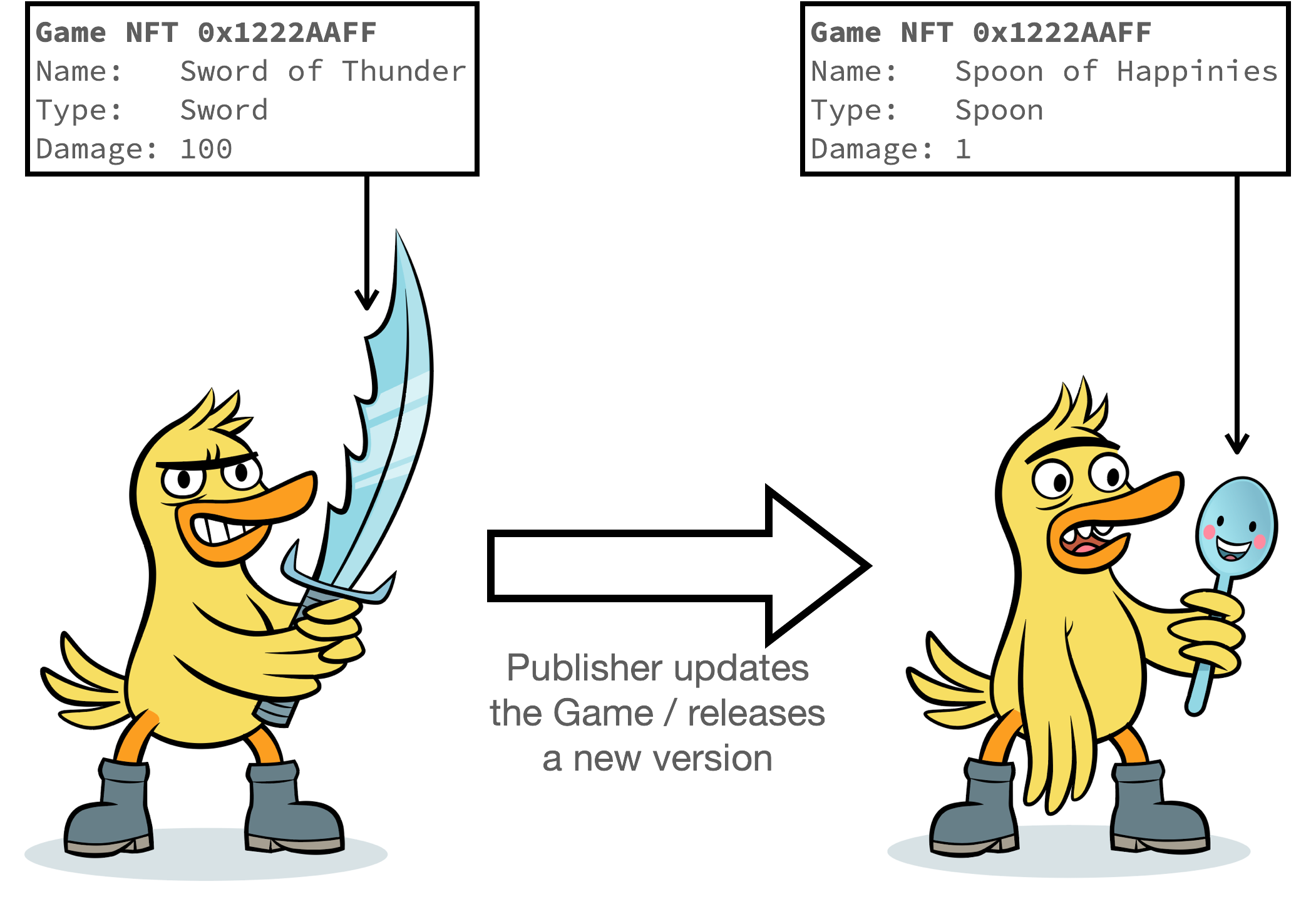

Most of the games that rely on Web3 technologies today use NFTs to represent in-game assets and “store them on a blockchain”. The promise here is that these NFTs belong to the players and not to the game, meaning they cannot be “taken away” or altered by the game publisher. Although this sounds very appealing at first glance, the reality is somewhat different: essentially, a separate NFT type is defined for each game today. This means that each NFT is closely tied to a specific game or ecosystem, and even if the player is the legal owner of the NFT, it only has value as long as the game exists. Additionally, an NFT does not contain information such as the data of an image (e.g., in the case of a skin) but rather a URL (a link) to the actual data behind the NFT. There is nothing to prevent the game developer from changing the URL or changing the contents stored at this URL to point to different data in the future. Therefore, it could even happen that the magical sword you earned after hours of gameplay suddenly has much worse stats next month. Sure, it belongs to the player, but ownership is completely irrelevant if the sword is suddenly no stronger than a spoon in the game. The argument that no publisher would ever do this is not entirely correct. After all, especially in the area of micropayments and loot boxes, we have seen too many things in recent years that supposedly no publisher would ever do.

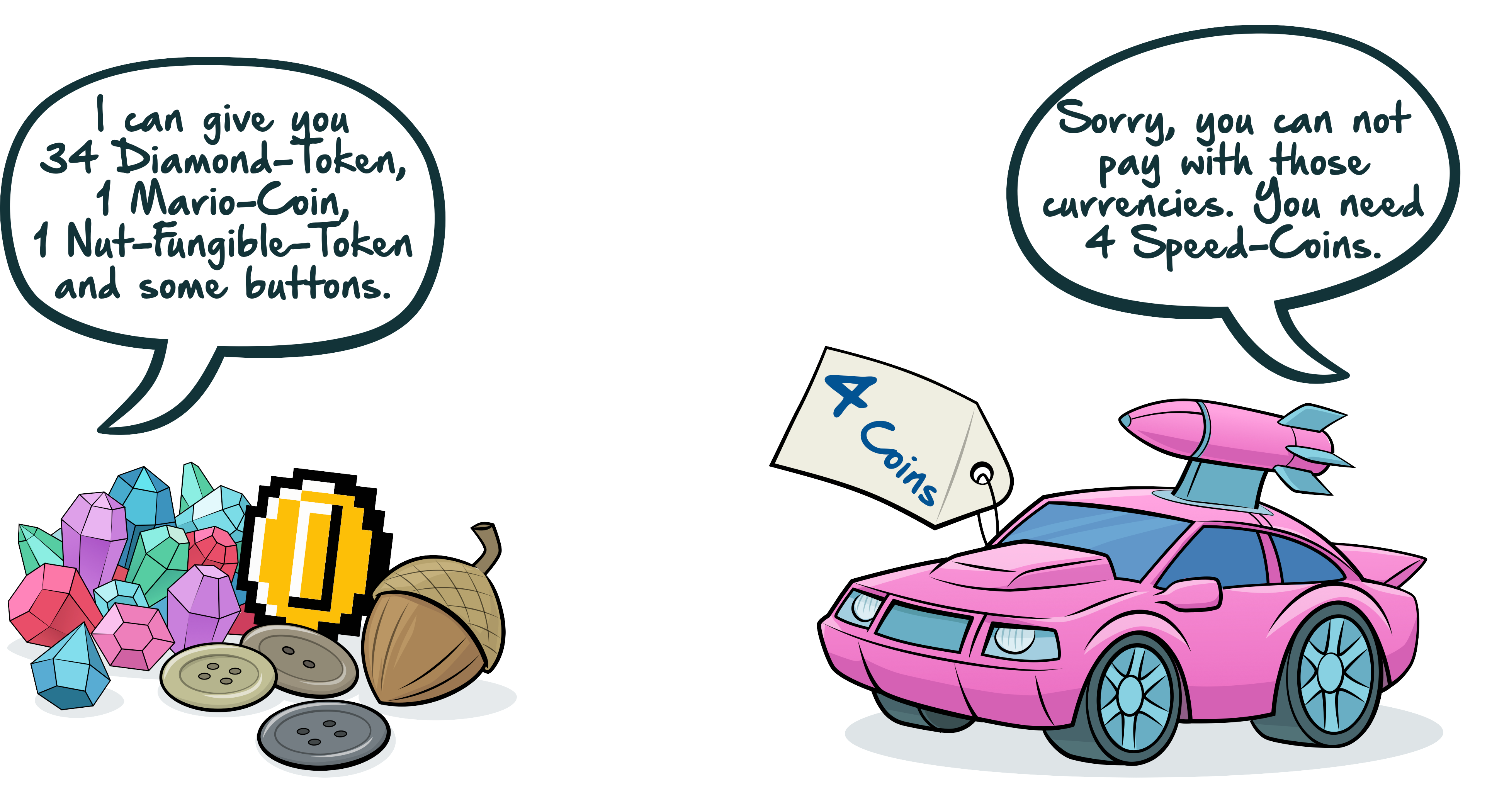

In addition to managing game assets such as items or skins, many of these points also apply to digital currencies used in computer games today. These are currently centrally managed by companies like Electronic Arts (EA) and are often tied to individual games. For example, you cannot use FIFA’s currency to transact in another EA game. Here, too, an NFT-based coin for micropayments would be advantageous. And even if game publishers are unwilling to share such a coin, each publisher should at least offer a coin that spans their games. Another advantage is that surplus coins could easily be exchanged back into real currency (fiat currency) via an exchange like Coinbase .

Based on these points, the use of NFTs for managing game assets and their ownership can be broken down into the following advantages and disadvantages:

Advantages:

- NFTs are standardized through ERC-721

- Ownership of assets can be transparently and securely represented by NFTs

- NFTs can be realized on various platforms ( Hedera , Ethereum , …) based on the NFT standard. A vendor lock-in can thus be avoided by doing so. With an NFT bridge, a token type can even be deployed to multiple platforms

- NFTs are now well-established in the technology world and are successfully used in various areas

- NFTs can be exchanged for real currency (fiat currency) via an exchange

Disadvantages:

- There is no global type for NFTs that can be used for games or a standardization of how NFTs for games should look

- The actual assets are still with the game developers and can be mutated or even removed

- There are no good ways to use and manage NFTs across different games

Next Iteration of Gaming NFTs

The disadvantages mentioned are technical and organizational and can be easily negated through various measures. In the following, I would like to present how the future of gaming with the use of NFTs could look. There are various ideas that, when combined, define a transparent and open system that provides standardized and independent management of game asset ownership for both players and game developers. Since there are various concepts and potential iterations, I will present them individually.

Extending the NFT Standard

While the NFT standard, as defined in ERC-721 , is already mature enough to clarify asset ownership, some important aspects are missing to make NFTs ideally usable in games. From my perspective, there are three important extensions that can make NFTs useful for games. These extensions relate to the topics of locking, metadata, and multi-token contracts. A concrete idea of how an interface for a game NFT could look will be provided later in this article.

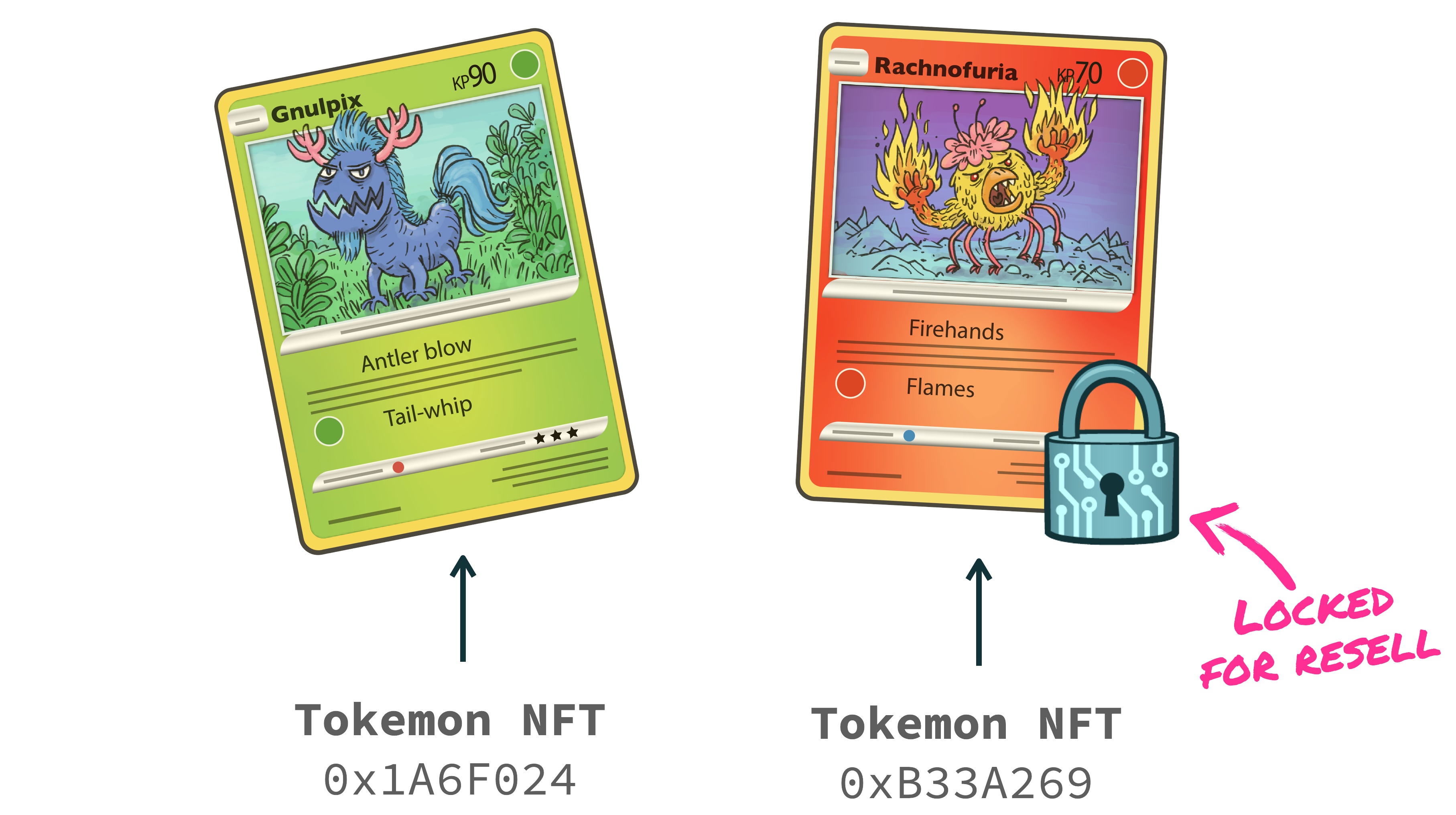

Locking of NFTs

For NFTs in games, it makes sense to lock assets. This locking prohibits an NFT from being traded, i.e., from changing owners. This is important to make NFTs usable in official competitions, for example. Imagine a digital trading card game where each card is implemented as an NFT. You must define which cards you want to use to participate in a game or tournament. These cards must not be traded during the tournament, as this would allow registered cards to no longer be in the player’s possession at a later time. Another example could be graffiti that you get in a skateboarding game. The corresponding NFT must not be sold as long as you have the graphic as an additional design on your skateboard. Once the graphic is no longer actively used in the game, the NFT can be unlocked and thus sold. ERC-6982 already defines events for locking NFTs. However, for games, this should be extended further.

NFT metadata

Besides locking, NFTs for computer games must contain additional metadata. This metadata is used to better determine the type of the underlying asset. Only in this way will it be possible for an NFT to be used in multiple games. Knowing whether an NFT represents a graphic or a 3D model is essential to give players meaningful access to their compatible NFTs within a game. There should certainly be a general tag as metadata that, similar to the MIME type, determines the kind of NFT (graphic, 3D model, sound, achievement). However, this will certainly not be enough. For graphics, the format and possibly the resolution must also be known. All this should be viewable within the NFT as metadata. This allows a game to quickly filter the cross-game NFTs in a player’s possession to display NFTs compatible with the game, regardless of which game they come from.

Multi-Token support

Once NFTs are used in multiple games, locking becomes even more complicated. In this case, an NFT must be lockable per game/application, and the definition in ERC-6982 is no longer sufficient. An application should not have to check the lock status of a foreign NFT in an endless loop. However, to manage a variety of different tokens from various sources, there is already an approach in the form of an Ethereum Improvement Proposal: with the Multi-Token Contract EIP-1155 , it should be possible to manage multiple tokens. An interesting article on this topic can be found here . Whether this is the right approach to manage various NFTs from different games or whether it requires an entirely different interface is not to be clarified here. What is important is that these functions are necessary to use NFTs meaningfully across multiple games.

How a standard could look like

In the following section, I will present the first idea of how a standardized interface for gaming NFTs could look. It should be noted that this is only a first draft with simplified code, and much discussion is needed to turn this draft into a sensible, sustainable, and secure standard for NFTs in computer games. The interfaces shown here are based on ERC-721 (NFT standard) and ERC-165 (Standard Interface Detection) :

interface GameTokens {

// returns the total amount of tokens for a game

function totalSupply(address game) returns (uint256);

// returns the total amount of tokens for a game for a given tag

function totalSupplyForTag(address game, string tag) returns (uint256);

// returns the tokenId of a game at a given `index`

function tokenByIndex(address game, uint256 index) returns (uint256);

// returns the tokenId of a game and tag at a given `index`

function tokenByIndexForTag(address game, string tag, uint256 index) returns (uint256);

// returns the owner of a token of a specific game

function ownerOf(address game, uint256 tokenId) returns (address);

// returns the total amount of tokens for a game owned by an owner

function balanceOf(address owner, address game) returns (uint256);

// returns the total amount of tokens for a game and a specific tag owned by an owner

function balanceOf(address owner, address game, string tag) returns (uint256);

// returns the tokenId of a game owned by `owner` at a given `index` of its token list

function OfOwnerByIndexForGame(address owner, uint256 index, address game) returns (uint256)

// returns the tokenId of a game owned by `owner` at a given `index` of its token list

function OfOwnerByIndexForGameAndTag(address owner, uint256 index, address game, String tag) returns (uint256)

// Only available for game admin (and contract admin)

// lock a non-fungible token of a specific game

function lock(address game, uint256 indexed tokenId);

// Only available for game admin (and contract admin)

// lock a non-fungible token of a specific game

function unlock(address game, uint256 indexed tokenId);

// Only available for contract admin

// transfers token by id of a game from an owner to another owner

function transferFrom(address from, address to, address game, uint256 tokenId);

}

interface GameToken {

// returns the name of the token type for a specific game

function name(address game) returns (string);

// returns the uri of the game

function gameURI(address game) returns (string);

// returns the description of the game

function description(address game) returns (string);

// returns the owner

function owner(uint256 tokenId) returns (address);

// returns true if locked

function isLocked(uint256 tokenId) returns (bool);

// returns all games that have currently locked the token

function lockedBy(uint256 tokenId) returns (address[]);

// returns the uri to the asset

function tokenURI(uint256 _okenId) returns (string);

// returns all tags of the token

function getTags() returns (string[]);

}Feedback on the design of the interface and its functions is always welcome.

Storing Metadata of Tokens

As described a token that is stored in a distributed ledger like Hedera or Ethereum belongs to an individual entity or person that is specified by an account. The game asset bound to the NFT is not a direct part of the NFT. Distributed ledgers are not made to store that amount of data. Instead, each NFT provides a link to the actual asset. Generally, that is defined as a URI that can link to the actual asset. A URI could look like this:

https://noobisoft.com/raving-habbits/03d5aa7d7a56de8a6de638aa6d.svg

As you can see, the file is hosted under the noobisoft.com domain. That fictive game publisher might use that domain to store all available assets by a game (in this case, the fictive game “Raving Habbits”). Since the file is stored on the game company’s server, the company has full access and can quickly mutate or delete it without needing the agreement of the NFT owner. Sadly, this problem is not transparent for most NFT owners or game developers - or NFT publishers in general - and will often be ignored.

New technologies and protocols like IPFS (InterPlanetary File System) offer a significant advantage here. Using the IPFS protocol, assets can be stored decentrally, ensuring the content remains accessible and immutable . Each asset is assigned a unique content identifier (CID), which links to the data regardless of its location. The unique IPFS-based URI for an asset could look like this:

ipfs://bafybeibnsoufr2renqzsh347nrx54wcubt5lgkeivez63xvivplfwhtpym/asset.svg

By doing so, even if the original server goes offline or the company decides to remove the file, the asset can still be retrieved from the IPFS network. This decentralization enhances the security and permanence of the NFT assets. It ensures that they cannot be tampered with, thereby preserving their integrity and value over time.

Moving to an Open Community

In addition to the technical extensions to the NFT standard, game publishers must coordinate further. Regardless of the path taken in the future to define NFTs across games, there will be an owner of the smart contract. As commented in the interface, this owner requires certain administrative rights to intervene in case of an error or the disappearance (e.g., due to insolvency) of a game or publisher.

Here, I suggest an open foundation for game publishers. There are already many examples of such compositions, and only an open and transparent working group in which no member has more rights than another will enable the creation of a standard NFT for computer games. In open-source foundations like the Eclipse Foundation or the Linux Foundation , you can find many examples of how such working groups can be implemented and established sensibly, transparently, and on equal footing. Therefore, I propose a similar concept for a working group to define and manage an independent and interoperable NFT.

Next Steps

As you can see, many different points still need to be clarified before we can realize the future of computer games using Web3 and NFTs, as already prophesied by marketing today. It is essential to understand that technical implementations are only part of the solution, and the most critical step is for the gaming industry to come together to tackle the project jointly. By doing so, we can end up with transparent, fair, and publisher-independent token standards for gaming that will allow the industry to create new business models for the future of gaming.

I am excited to see if the industry can take on this mission and if we will finally see meaningful and sustainable use of (micro)transactions and NFT-based assets in computer games. Suppose gaming industry members are interested in discussing the abovementioned ideas and technologies. In that case, I’m happy to help with my expertise in web3 technology as a Hedera core committer and my knowledge in foundations and working groups as a board member of the Eclipse Foundation.

Hendrik Ebbers

Hendrik Ebbers is the founder of Open Elements. He is a Java champion, a member of JSR expert groups and a JavaOne rockstar. Hendrik is a member of the Eclipse JakartaEE working group (WG) and the Eclipse Adoptium WG. In addition, Hendrik Ebbers is a member of the Board of Directors of the Eclipse Foundation.