Every Six Months an Update: The Path to the Java Release Train

#Java

Since the release of Java 9 in 2017, new Java platform releases have been published through a new and much better-defined release train. Unfortunately, the statements about the various changes and improvements to the release train were often vague, and there were even false rumors in the community. Oracle, in particular, has delivered poor public relations and did not describe the new release train as transparently and cleanly as it should have. With the release of Java 17, further changes have been made to the release train, and I would like to use this post to describe the specific process.

The good old days

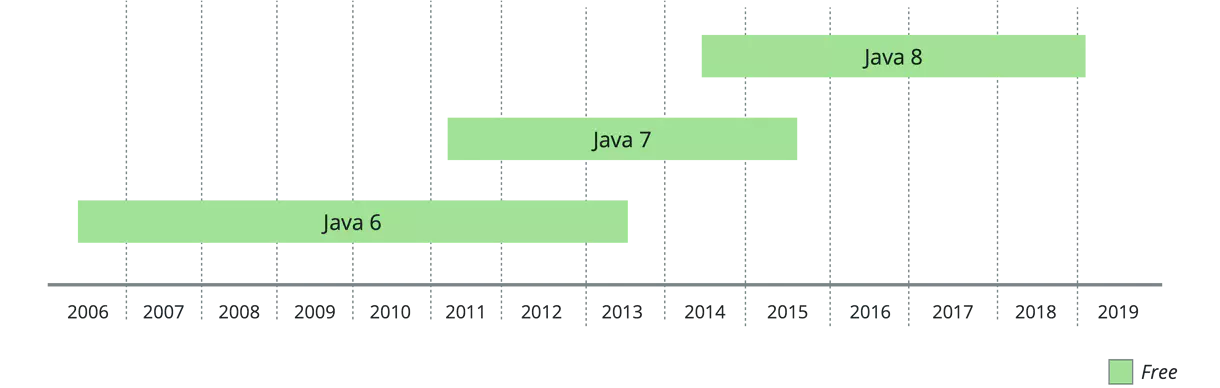

Before we look at the new release train, it makes sense to take a look at the releases of older Java versions. The following diagram shows the release date and lifecycle of Java 6, 7, and 8. The lifecycle of the versions is defined by the availability of free security updates for the respective version. Once there are no more free updates for a version, its lifecycle ends in the diagram.

In the diagram, you can see different points. It is important to note that there is always a period during which at least two releases with security updates are supported. This time serves users of the platform as a period to migrate their applications to the newer Java version. Additionally, the intervals between the releases of new versions vary. This is because these Java versions were released as soon as all the features defined for the respective version were implemented.

For each of these old Java versions, the features to be implemented were defined within a Java Specification Request (JSR) in the Java Community Process (JCP). For example, for Java 8, you can find a list of individual features under JSR 337 in Section 3. These are also specified as JSRs, with the introduction of lambda expressions in Java defined in JSR 335 and the Date & Time API in JSR 310.

Since it was predetermined which JSRs should be implemented in a new Java version, the release date could never be definitively set. This sometimes led to long intervals between the releases of the versions.

It is also important to note that these releases are not specific to Oracle’s JDK. All these versions are created in OpenJDK. Thus, any Java vendor can offer a build of their runtime with the current version without functional differences.

More Dynamics Through Faster Releases

With Java 9, this approach has changed significantly. Instead of long-lasting releases with an indefinite release date and lifecycle, a new major release of the Java platform now appears every six months. This happens as before in OpenJDK, but the sources of OpenJDK have been completely migrated to GitHub since Java 17, where the exact workflows can be much better understood. Since the release date of a release is fixed, the features can no longer be determined in advance. Instead, a new Java version contains all the features completed by that date. These features are defined as JDK Enhancement Proposals (JEPs) and can all be viewed on the OpenJDK website . These JEPs can be thought of similarly to Epic Issues. From Java 10 onwards, you can also see the list of JEPs included in the release on the respective release pages ( see the example for Java 11 ).

Feature Previews

Since some of these features take longer to develop and have a significant impact on the Java platform, the preview and incubator status was introduced for JEPs. New APIs can already land in Java versions for testing through the latter before they become a final part of the Java class library in a future version. Such APIs are in a special incubator package and are only moved to their correct package with their final release. The preview status can be used to make new language features of the Java platform available in advance. Such features must be activated via a command-line parameter:

$ javac HelloWorld.java

$ javac --release 14 --enable-preview HelloWorld.java

$ java --enable-preview HelloWorldLong-Term Support and Critical Patch Updates

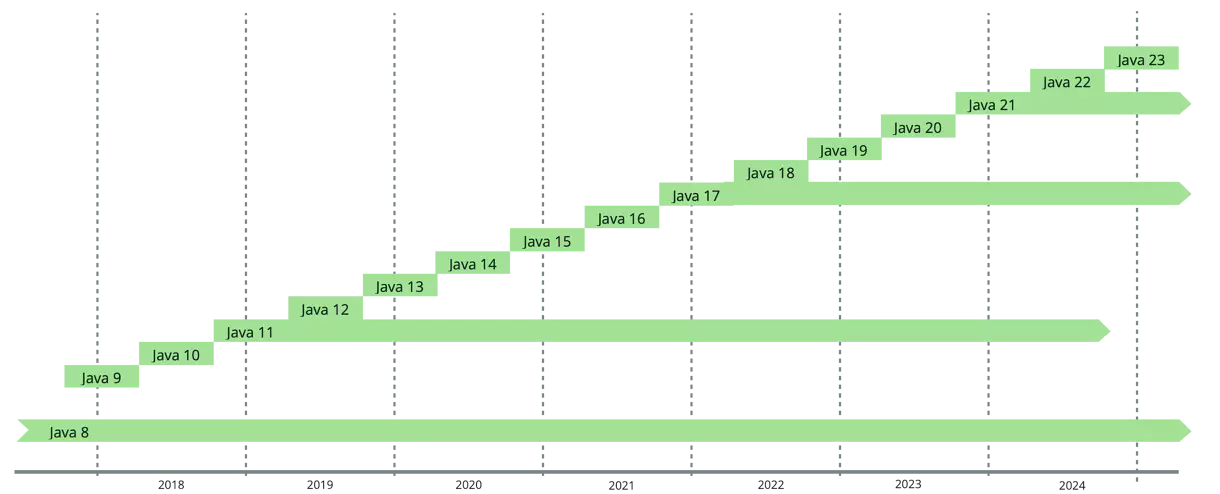

With a new release every six months, the lifespan of Java versions has changed significantly. Now, there is a distinction between Long-Term Support (LTS) and regular (non-LTS) versions. The latter have a lifespan of exactly six months until the release of the next version. For example, Java 14 had a lifespan from March 2020 to September 2020. LTS-labeled versions are maintained longer in OpenJDK and receive security updates over an extended period.

For the LTS release Java 17, updates are expected until 2027. A good overview of the LTS versions is provided by Eclipse Adoptium in the support overview . Although LTS updates do not contain new features, they fix all known security vulnerabilities. Therefore, such releases are also called Critical Patch Updates (CPU). For Java versions that are not defined as LTS versions, two planned CPU releases appear. For example, for Java 16, version 16.0.1 was released as a CPU in April 2021 and version 16.0.2 in July 2021 after the first release in March 2021. With the release of Java 17, it was decided that there would be a new LTS release of Java every two years. Consequently, Java 21 will be the next LTS release in September 2023.

Based on these definitions, the release graph of Java versions since Java 9 looks as follows:

Since all work is done in OpenJDK, the release date of individual Java distributions may vary slightly. Once the release is published in OpenJDK, the work to create the distributions like Eclipse Temurin, Oracle JDK, or Azul Zulu begins. Each manufacturer is free to extend the sources of OpenJDK with additional features to differentiate themselves. Some, like Azul or Bellsoft, bundle JavaFX in their builds.

In earlier versions, Oracle, in particular, tried to differentiate itself from other OpenJDK builds with tools like WebStart or Mission Control. However, this led to compatibility issues within the community and is fortunately no longer commonly practiced today.

Hendrik Ebbers

Hendrik Ebbers is the founder of Open Elements. He is a Java champion, a member of JSR expert groups and a JavaOne rockstar. Hendrik is a member of the Eclipse JakartaEE working group (WG) and the Eclipse Adoptium WG. In addition, Hendrik Ebbers is a member of the Board of Directors of the Eclipse Foundation.