Write Once, Run Anywhere - how good is Java's Backwards Compatibility?

#Java

With the slogan “Write Once, Run Anywhere” (WORA), Sun Microsystems promoted the Java platform starting in 1995. This slogan combined two different advantages of Java: By using the JVM (Java Virtual Machine), compiled programs can run on all platforms where a JVM is available. For example, a Java application compiled on Windows can run seamlessly on Linux within a JVM.

The second aspect of the slogan is Java’s backward compatibility. Software compiled with one Java version should run without issues on future Java versions. However, this promise has changed over the years.

Backward Compatibility through Private APIs in the JCL

Backward compatibility in Java has always been enabled by separating the public and private APIs in the Java Class Library (JCL).

The JCL includes all classes of the Java API that we work with every day, such as java.lang.String or java.util.List.

But it also contains more exotic classes like sun.misc.Unsafe.

Together with the Java Virtual Machine (JVM) and various tools like the Java compiler (javac), the JCL defines the JDK for JavaSE that developers use daily.

The private API of the JCL is on the classpath but should never be used directly by applications.

Internal changes in the OpenJDK are often implemented in this area, which could lead to potential changes in the interfaces of the private API.

Generally, all classes in the JCL whose packages do not start with java.* or javax.* belong to the private API.

Since some Java distributions include JavaFX, you can add javafx.* to this list.

Software that used classes from the private API at compile-time or runtime was at risk of becoming non-functional with every (major) release of Java. While the usage at compile-time could be detected directly, runtime usage through reflection or transitive dependencies sometimes led to unexpected problems in production.

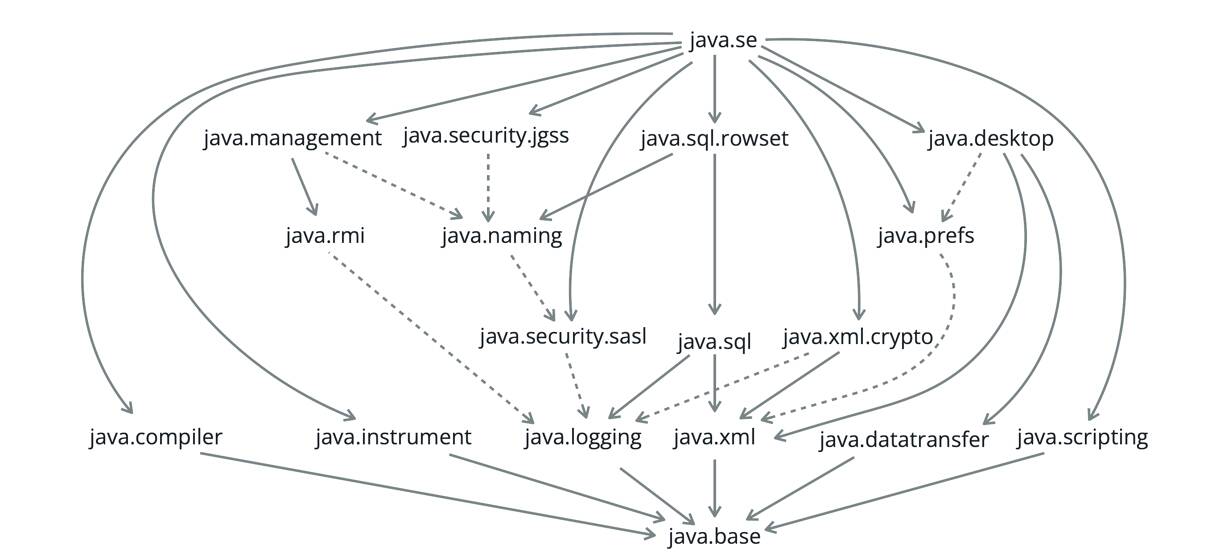

However, this changed with Java 9 and the introduction of the module system. The module system allows hiding APIs from the outside world, making them usable only within their own module. This enabled the complete hiding of Java’s private APIs.

Since many programs and libraries used these private APIs, this change in Java 9 would have led to immense refactoring.

Therefore, the OpenJDK decided that the private APIs from Java 9 to Java 15 could still be used, with only a warning issued when software accesses private APIs.

For this, the illegal-access parameter was introduced, which was set to warn by default in Java 9 to 15.

This parameter could be easily changed at the JVM startup as a command-line argument.

In these versions, you could also ensure that a Java program could not use the JCL’s private APIs by adding --illegal-access=deny.

This became the default behavior in JDK 16.

Here, you must actively set the flag to warn if you want to allow your application to use private APIs.

However, with the LTS release of Java 17, this option was completely removed.

The values permit, warn, and debug were removed for the illegal-access flag, making it impossible to allow general access to private APIs.

If you still need to use private APIs with Java 17, you can enable this for specific modules using the --add-opens flag or the Add-Opens attribute in the manifest.

Changes in Tools or the JVM

Changes in the tools or the JVM can also affect Java’s backward compatibility.

For example, with Java 10, the Java language was extended with the use of var through JEP 286

.

This allows omitting the explicit type declaration for a variable when the compiler can infer it.

Here’s an example:

var list = new ArrayList<String>(); // infers ArrayList<String>

var stream = list.stream(); // infers Stream<String>

The introduction of var into the Java language had some implications.

Although var was not added as a keyword to the Java syntax, allowing it to still be used as a variable name, its status in the Java language is defined as a “Reserved Type Name” (see JEP 286

).

This means it is no longer possible to name classes or interfaces var, which, although rare, is a break in backward compatibility with Java.

Deprecated APIs for Maintaining Backward Compatibility

The first version of Java was released in 1996. Since both the Java programming language and programming paradigms have evolved significantly since then, many APIs in Java have been refactored. Patterns that were typical in 1996 are now considered outdated. Additionally, the OpenJDK developers occasionally make mistakes, leading to APIs that should no longer be used based on current knowledge.

To maintain Java’s backward compatibility, such APIs were not removed if they were part of the JCL’s public APIs.

Initially, the JavaDoc warned against using them and often suggested alternative APIs.

With the introduction of annotations in Java 1.5, this was further improved through the use of the @Deprecated annotation.

This annotation not only warns the user that an API should no longer be used but also causes the Java compiler to generate a warning (or an error, depending on the configuration).

IDEs today also highlight this prominently, making it easy to see if code is accessing APIs marked as deprecated.

Although this approach worked for a long time, more and more code in the OpenJDK became annotated with @Deprecated, requiring maintenance with every version and change.

The Java API also became increasingly bloated.

With the introduction of the Java module system and the division of the JCL into individual modules, other problems arose: Due to the many outdated code sections that were never removed, there were wild dependencies in the OpenJDK that could not be easily resolved.

Therefore, with Java 9, the @Deprecated annotation was extended with the forRemoval attribute.

This attribute indicates that an API annotated with @Deprecated(forRemoval=true) can be removed in a future version of Java.

With Java’s new release train and new versions every six months, this can happen very quickly.

Recent Java versions show that this is being utilized.

For example, the CORBA API, various interfaces under java.security.acl.*, or methods from java.lang.SecurityManager have been removed.

The java.lang.SecurityManager itself is even scheduled for complete removal from the JCL.

Tracking Changes

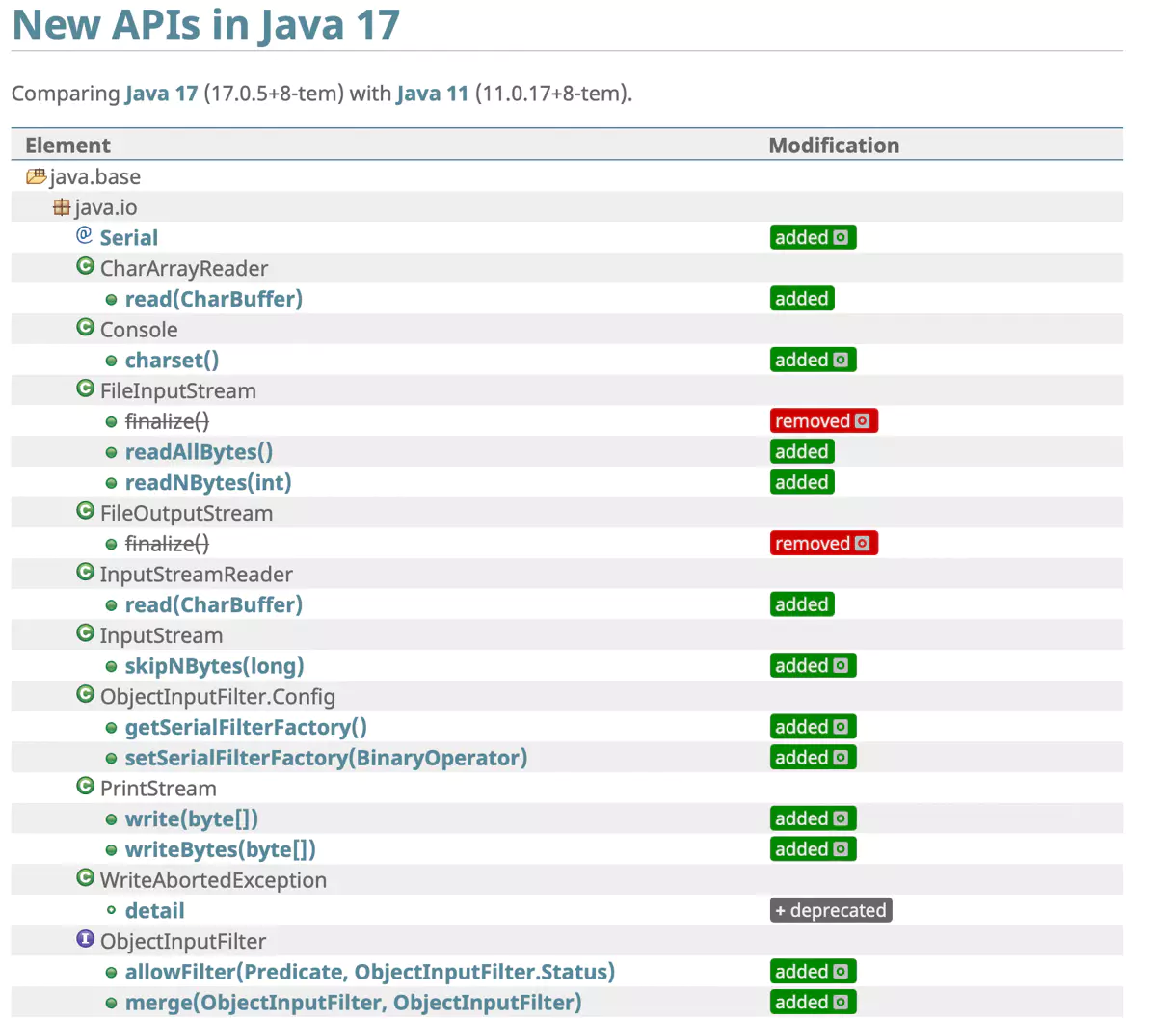

To review and assess the differences and changes between two Java versions, there is now the website javaalmanac.io

.

Here, all differences in the Java Class Library between two Java versions can be displayed.

Since not only versions with Long-term Support (LTS) are listed but all major releases since Java 1.0, you can start adapting your software even before a new LTS version of Java is released.

In addition to changes, the tool also shows all classes, functions, and other elements that have been annotated with @Deprecated.

What Does This Mean for Developers?

Java has shown that programming languages must eventually choose between innovative and agile development and constant backward compatibility. The older a language gets, the more legacy baggage it carries. Many parts of the API are no longer up-to-date and difficult to adapt to modern paradigms. Therefore, it makes sense for a language to shed some of its legacy baggage. Of course, users should not be forgotten, and these issues must be handled sensitively.

In my opinion, the people responsible for Java have handled this balancing act well by announcing the new concepts, such as removing deprecated APIs, over a long period.

They have also responded to criticism and feedback from the community.

The handling of the sun.misc.Unsafe class is certainly a good example.

Its removal from the OpenJDK was discussed for a very long time.

Additional features were also added to the OpenJDK for framework and library developers to ensure backward compatibility.

With Multi-Release JAR files ( JEP 238

), JARs can now contain specific classes for different Java versions, significantly increasing compatibility.

Nevertheless, such changes result in more work for developers who wait a long time before switching between Java versions. However, if you always upgrade to the latest LTS version of Java and are familiar with the concepts and tools described here, the work generally remains manageable.

Hendrik Ebbers

Hendrik Ebbers is the founder of Open Elements. He is a Java champion, a member of JSR expert groups and a JavaOne rockstar. Hendrik is a member of the Eclipse JakartaEE working group (WG) and the Eclipse Adoptium WG. In addition, Hendrik Ebbers is a member of the Board of Directors of the Eclipse Foundation.